For three hours under the starless Indian sky, I watched the flesh blister, char, and fall from the bones of the freshly deceased corpse. The body of what was, until just a few hours ago, a person capable of love, hate, jealousy, generosity and every other characteristic associated with human consciousness. Now, nothing more than insignificant tissue atomising in the intense heat of the raging flame. Varanasi’s Burning Ghats.

And this was not the only one. From where I sat on the sandstone staircase of Varanasi Harischandra Ghat on the western bank of the Ganges river, several identical Pyres were also purifying the deceased fathers, mothers, sons, daughters, brothers and sisters of the surrounding crowd. The remains of which would soon silt the tributaries of India’s spiritual artery. Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats.

- Facing Mortality

- Unavailable on Netflix

- It’s Just A Thing

- Legendary Loopholes

- Complexity

- No Wifi, No Problem

- Where are you From?

- Generous Friends

- The Schpeel

- A Novel Procession

- Oh My Ghat

- Stairway To Heaven

- Raj

- Caste Down

- The Schpeel Pt.2

- Uncredible Sources

- The Disrespectful Doms

- Spiritually Bankrupt

- Misplaced Entitlement

- Uncle

- Under Pressure

- Wheres My Money?

- Time to Leave

- You Win Some

- Clueless

- Manikarnika Ghat Take 2

- The Process

- Cremation Pyres

- Ashes To Ashes

- The Cycle of Degeneracy

- Conclusion

Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats.

Facing Mortality

Mesmerised and humbled by the stark reminder of my mortality, I remained fixated, unable to break my gaze on the elemental consumption, reclaiming the fat, bone and muscle before me. All while the abstract notions of life, death and the duality of our precarious human predicament raced through my unsettled mind.

And although the possibility of exit from the crushing weight of this existential experience lay just meters away, there was no escape. I had become hopelessly locked into the psychic maze of reflection this novel spectacle had ignited in the grey matter still oxygenated behind my eyes.

Unavailable on Netflix

As a Westerner, the opportunity to sit with death in such an intimate setting was as foreign to me as the murmurs in Hindu I would intermittently register from the surrounding mourners. Or the strange cultural traditions I continued to observe them perform. Ones enacted in this same place since the 5th century BCE.

Where I come from, England, death has become a significant cultural taboo. Not only do bodies quickly disappear from sight, but the sullen topic avoided from conversation almost entirely. Even for those approaching the final stages of their lives, touching on the matter instils too much anxiety in those who will remain for it to be open for discussion. The West’s denial of death is comparably intense to the seething heat of the cremations, forcing me to squint my eyes and shield my face.

So death, the West’s dirty little secret, remains hidden in hospitals and behind church doors. Only to see the light of day when a family member inevitably succumbs to the morbid law. There are certainly no opportunities to be present with it in such a raw and confronting manner as is possible here in Varanasi.

It’s Just A Thing

In India the concept of death takes a different form. As most of its 1.5 billion people actively engage in some form of religious practice, for them, the physical decimation of our material bodies is little more than a transitory stage in a universal play of consciousness. One far loftier than any single egocentric human lifecycle can comprehend. A stance contrary to the Western perspective, which spells only the eternal end of one self-important ego.

For the Hindus, who comprise 80% of the country’s enormous population. Death is part of a cycle of reincarnation, otherwise known as Samsara. According to this belief, all living things have an Atman, a piece of Brahman (God), or a spirit or soul. Which moves on into a new body after death.

The atman can enter the body of any living thing, such as a plant, animal or human. And once a living being dies, its atman will be reborn or reincarnated into a different body depending on its Karma from its previous life. For example, if a person has good Karma, then their atman will be reborn into something better.

Legendary Loopholes

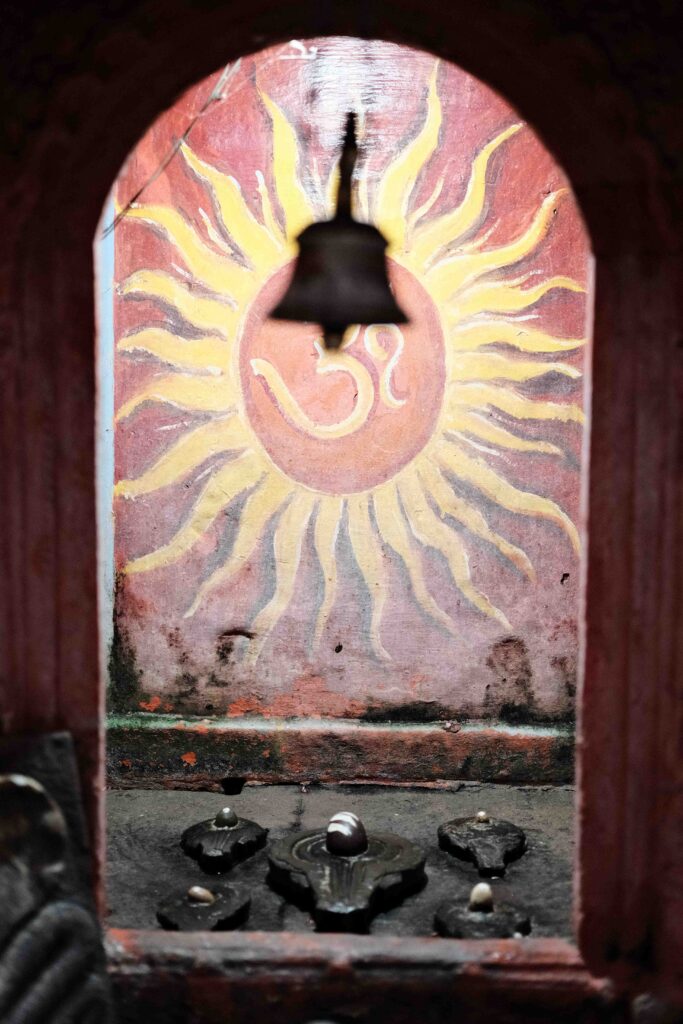

However, like a loophole in a legal system saving criminals from sentencing, there appears to be a way around spending one’s life pursuing Karma for the Hindu. A little like the Christian repenting his sins and accepting Jesus before death. The Mythology ensures that by cremating a body on the banks of the Ganges with the sacred flame, it will achieve Moksha. A get-out-of-jail-free card of sorts for those sceptical about the selflessness of their earthly actions.

As the legend goes, Mata Sati (A Hindu Goddess) set her body ablaze in an act of self-immolation in retaliation to an attempt by Raja Daksh Prajapati (one of the sons of Lord Brahma) to humiliate Lord Shiva in a Yagya practised by Daksh. Following this, Lord Shiva then took her burning body to the Himalayas.

On seeing the unending sorrow of Lord Shiva, Vishnu sent the Divine Chakra to cut the body into 51 parts, which then fell to earth called “Ekannya Shaktipeeth”. Shiva then established Shakti Peeth wherever Sati’s body had fallen. Her ear ornament fell at Manikarnika Ghat, now one of the fifty-one holy sites enriched with the presence of the deity.

Complexity

Without diverging down the complex path of Hindu mythology. To summarise, those cremated at one of the two cremation ghats in Varanasi, will end their lifecycle and achieve Moksha. With or without the presence of several lifecycles of good karma. Not a bad deal, right?

So, with this promise of spiritual liberation despite the number of babies you may have eaten. In a country with such an enormous population, the belief means there are inevitably large numbers of people making their way to the city for the promise of reaching Nirvana. The figure estimated at around 20,000 each year.

And wherever hope exists in India, you are sure to discover entrepreneurial individuals ready to capitalise from this belief. As I would learn the following day on my visit to the larger, more esteemed Manikarnika cremation ghat.

No Wifi, No Problem

The following morning, as I made my way towards the Manikarnika Ghat through the decaying ancient streets, I decided to stop for a coffee. Before proceeding into what I expected to be an active morning of photography and interviews. So, any extra energy I could muster before my arrival would be beneficial. Fortunately, in this place, you are never far from a fresh brew on the boil.

As I exited one of the old town’s narrow alleys onto an open street leading to the famous Sheetla Ghat. Where the Ganga Atari ritual (Prayer to the Ganges) takes place each evening. I noticed the perfect place for my cuppa. One where I could enjoy observing the many interesting characters that had already begun to line the streets under the early morning’s intensifying heat. Honestly, a TV is not necessary in India. More entertainment is available in witnessing the obscure and often questionable actions of the people and animals. There is always something enjoyable on.

However, before I could sit down with my terracotta cup of fresh milk and instant coffee, a man approached. Seemingly intent on becoming my friend before we had even introduced ourselves. “Hello”, “Where are you from?”, he opened with, with an open tone. The question those who have been to India before will know all too well. Because on any given day, a Caucasian can expect to answer it a hundred times.

Where are you From?

“Hi, I am from England”, I responded. “My name is David, it’s nice to meet you”, saving him the effort of the predictable next question. The proceeding seconds of the interaction would now highlight this individual’s intent. Although, I had already deciphered this based on his scruffy, unwashed appearance and overly friendly demeanour.

Because here in India, people will often engage with a Caucasian for one of two reasons. Of course, there are cases which exist beyond these. However, in most scenarios, the person or people want only one of two things from you. Either a selfy or to leave with as much of your money in their pocket as possible.

Think of the old-style cartoons where a hungry character will hallucinate another as a tasty sausage or pie on legs. The perspective of many Indians is very much the same when they see a white person. However, instead of appearing as a tasty meal, we take the form of walking ATMs. Ones anyone can withdraw a deposit from if only they give us enough grief and hassle.

Generous Friends

Unfortunately, this was to be a case of the latter. Nevertheless, I continued to entertain the man as he unceasingly, and without due cause, proceeded to sell his character as honest and trustworthy.

Another common tactic of these people is to spin a story of how they have strong connections with individuals from Europe or North America. In his case, I had to hear about his British friend. One that had supposedly given him ten thousand pounds during COVID-19 to help him and his family.

A tactic used to make any future donation I make seem small next to this very generous British man. However, it only made me less inclined to give him something. After all, no one gave me 10k during the pandemic. And 10k here in India easily equates to 50k or more back home. The charitable donation even bought the man, whose name I had now discovered was Pawan, a house. And had also allowed him to start a successful business selling flowers. So I wasn’t entirely sure why he was working me for my money.

The Schpeel

“What are you doing here in Varanasi? Do you want a boat ride?” he continued, attempting to structure our relationship with him as my service provider. “Actually, I am going to see the Cremation Ghat today,” I replied, cautiously. “Ah, perfect”, replied Pawan. “I have many friends at the ghats. I can introduce you to them.” “And do not worry, I don’t want any money. I only want you to enjoy Varanasi and for me to gain good Karma for helping a traveller.”

His speech was grade-A bullshit through and through. Nevertheless, if he could introduce me to a few crucial characters for interviews at the ghat, perhaps he could help after all. So, against my better judgment, I agreed for him to accompany me.

A Novel Procession

Fortunately, the walk to the Ghats wasn’t far, meaning I didn’t need to engage with him for too long. And it took us down several more aesthetically pleasing streets. Ones characteristic of Varanasi, which the camera lapped up joyously. However, the most notable thing observed en route first came as a distant chant echoing along the walls of the narrow brick-and-mortar corridors.

At first, I wasn’t sure what to make of it. The sound was brand new and continued to increase in volume. In anticipation, I stepped aside, also allowing a bulky, well-fed cow and several mopeds to pass. I then waited to see what approached next.

Soon enough, beyond the piercing sound of those moped horns that always rang as if the entire world would be oblivious to them without it, the words Ram Naam Sathya Hain (The name of Lord Ram is the truth) began taking an audible form.

Following this came a frenzied procession of people at a pace that had them nearly running down the street. The fiasco of this group would’ve been a sight to behold in itself. However, I noticed a number of the group were also carrying something on their shoulders. The energy of the hysterical gang was of a twisted, morbid nature. Meaning something wasn’t right. But I still couldn’t figure out exactly what it was.

However, the confusion lasted only moments as soon the object riding on their frenzied frames became clear. At first glance, what had appeared nothing more than a colourful amalgamation of glittering fabrics and vivid flowers revealed its true melancholy. It was no joyous sacrifice to Shiva or other harmless cultural offering. Instead, It was a lifeless body, one now closing the gap towards its fragmentary dissolution.

Oh My Ghat

After letting the procession pass and a more twists and turns around the claustrophobic streets. Dodging scores of stray dogs, herds of free-roaming cattle and the pools of excrement they inevitably leave behind. I soon noticed holes in the walls where merchants were selling firewood. We were close. And sure enough, as I peered down the alley, beyond the linen draped figures lining the pavement, I noticed a break in the battered ad hoc architecture.

“Here, we have arrived”, explained Pawan, earning every penny of his expected payout. The opening from the residential street led us to a bigger space full of mourners, business people, priests, and splinters of scattered wood. On the left-hand side was a dedicated wood store two stories tall. Its contents ready to purify and clean the souls of those who would soon leave this place as ash. And, to the right stood a large building with different sections, including another ground-floor wood store, a temple, and a first-floor crematorium.

Under the flight of stairs which led to the temple and crematorium, I noticed a barber at work. Although, unlike others in his profession, this man needed only a single razor to perform his job. Because just like his family had done for generations before him, it was his duty to shave the heads of the eldest sons who arrived here to cremate their parents. Some in the process of loosing their hair whilst I passed. Next to him, a dark alley cutting through the building led to the cremation Ghat, where I could see two active pyres at various stages of the cremation process.

Stairway To Heaven

“Follow me. I want to introduce you to someone”, murmured Pawan after finishing a short conversation with one of the stern, leathered-faced wood merchants. Now, ascending the steps towards the first-floor crematorium. And turning back to confirm I was still in pursuit.

At the top of the staircase and the entrance to the crematorium, a conflicting scene faced me. Because there was a panoramic view of the river Ganges, which, if not for the layers of remains from a thousand different bodies, would have been a perfect location for a romantic restaurant. Nevertheless, despite the romantic view, the place felt cold and isolated. There were definitely no vibrations of love to register here. No, this space belonged to death, and death alone. The centuries of it as thick in the air as the smoke rising from the still glowing embers of the deceased lining its floor.

Raj

We continued through the crematorium. The ash compressing underfoot like freshly settled snow. To my side, a stray dog chewing on what was undoubtedly human remains. And, everywhere discarded confectionary that once meant something to someone. At the end of the room between the two columns of terminal beds, was man standing amidst the smouldering embers and thick grey smoke. One that Pawan had hurriedly raced to meet to discuss something in Hindi before I could introduce myself.

“Hello, I hear you want to make a documentary about the ghats?” the obscured figure said. “Are you a professional?”. “I’m an independent journalist”, I replied. “And yes, I want to write an article about the burning ghats here in Varanasi.” “OK”, he replied, “but you must make a donation”. Great, I’ve willingly walked into a scam. Nevertheless, despite knowing this was bullshit, I nodded along and agreed accordingly. Because I did want to talk to and photograph the Doms (the caste of workers that manage the place) and to get his buy-in, I had to play the fool.

Caste Down

Over the next ten minutes, we would continue our conversation amongst the morbid winter wonderland. Fortunately, on a quiet day, as no cremations were taking place inside the building to interrupt us. I discovered that Raj had been working at the cremation Ghat for the last eight years after leaving a job as a carer. When asked if he was happy with his work, he surprisingly replied, “Yes, I want to do this job because I belong in this job”. And further stated, “this job is crucial to the community, and I wouldn’t change it”.

We touched on the caste system in India and how he felt about being a Dom. Again, he seemed unfazed, if not proud, of belonging to his “untouchable” caste. We then briefly discussed the rituals and customs surrounding the cremations. However, because I was engaging in a scam, It wasn’t long before the hot air began blowing. And any useful or factual information became increasingly challenging to filter through. For example, another common tactic used by con men in India is the schpeel about Karma.

The Schpeel Pt.2

In this case, a person who wants you to “donate to a charitable cause”, AKA their back pockets. will go on and on about Karma, good deeds and high moral values. Basically, to spiritually blackmail you out of your cash. Fortunately, I had some experience with this in Bodh Gaya, so it was nothing new. However, I began to receive this much sooner than I would’ve liked. And despite efforts to steer the conversation towards topics relating to his personal experiences and outlooks, it became clear nothing credible would be attained from this source.

Additionally, just like Pawan’s tactic of using a 10k handout from a British man, I now had this man spouting some over-the-top figures for the price of wood (for the scam that was to come) that went well beyond the numbers I had conducted from my research. Claiming one kg cost 800 rupees when the price was far closer to 50. And I know it’s tempting to think, “Well, isn’t he the expert?”. Which you rightly should.

However, as I was to discover. The Doms care far less about their reputation and building good Karma than lining their wallets. A sensibility of entitlement unfortunately shared by many Indians. I was beginning to regret my decision to go with Pawan, who remained by our side the entire time, adding nothing to the conversation.

Uncredible Sources

No longer able to trust information from Raj. I continued to nod along with divided attention as he relayed more questionable facts about the Ghat and Karma. Now more interested in using my time to photograph the location than taking notes. Which was a devastating outcome because to have genuine points of view, experiences and quotes from the Doms to reference would’ve been a brilliant addition to this article. However, their only interests lay in scamming the foreigners that step into their domain. A fact my subsequent interactions would solidify.

“Come, now let me show you the sacred eternal fire,” said Raj impatiently. Despite my evident engagement in photo taking. My job seemingly of little importance to him. But I remained on my shot until I was content before following him down the stairs to the opposite side of the building.

The Disrespectful Doms

After passing the barber still shaving heads, we continued onto a balcony under the temple on the first floor. The crude design of the place made little sense. However, these days, I have stopped expecting anything in India to conform to the slither of rationality. And it was old, real old. Inside was a group of 5 men, lethargic, stoned, filthy, drunk, and all at varying levels of nakedness. These were the Doms, the protectors of the sacred flame and guardians of the passage to Moksha. A charming introduction to the community.

It was easy to see these guys knew they had a monopoly on the cremation processions. And this is true because, without a Dom present at the cremation, Moksha is unattainable. But imagine if your grandmother had just passed, and you needed to cremate her ASAP (before she started to smell and attract flies). And, you get to the funeral parlour to see your options for directors as a gaggle of men comparable to those commonly spotted on park benches clutching value bottles white cider in unwashed clothes. Not a pleasant way to send her off. And the lack of competition for providing the service only encouraging their apathy.

Raj and I stepped over a number of the indifferent men catching flies to get close to the fire. “This is the sacred flame,” he said, pointing to fragments of barely glowing embers on a thin rectangular wall overlooking the ghat. “This same fire has been kept lit here for the last 5000 years.” he continued. “Impressive, so it has never gone out?” I replied. “Not once”, Raj went on confidently. A questionable statement but a necessary allure for their business model.

Spiritually Bankrupt

Suddenly, an older, large-bellied Indian after struggling to stand up from the tribe, then approached. Just as dirty and half-naked as the rest. With only a robe tied around his waist and some ash spread across his forehead. “It’s now time for you to receive your blessing,” said Raj. Here we go, I thought. On the previous day, I had met another holy man who had expected me to kiss his feet, and this one wanted me to do the same. I let him put some ash on my forehead while he muttered something in Hindi without making eye contact, but there was no chance of submission.

“Ok, it’s now time to make your donation,” said Raj. But not before recieving the blessed opportunity to hear about the plight of the poor Indians who come here without money to be cremated. And how this selfless group of morally outstanding drunks surrounding me would go out of their way daily to support the sick and elderly in hospices. And help collect donations from the visiting rich Indians to help them achieve Moksha. I finaly understood why they all looked so lethargic.

“The average donation is between 5,000 and 10,000 rupees (£50-100)” stated Raj. The time had come for the long hard shaft of Varanasi’s spiritual trident to pay a visit to my behind.

The trouble was I knew taking photographs at this place was forbidden. And my style of photography isn’t exactly discreet. So I didn’t want to put myself in a position where I wasn’t going to get the shots I needed. Moreover, I wanted a set of portraits of the Doms. Meaning I had to hand over something. “Here’s 1,500”, begrudgingly delivering three 500 rupee bills into the greedy hand of the well-fed man.

Misplaced Entitlement

“No, you have to give more”. “Remember, this is for your Karma”, exclaimed Raj. “But this is all I can afford to give,” I said in disbelief (1,500 or £15 is no small donation in India). The attempt to push me for more continued for a few more minutes until they realised I would not hand over another Rupee. Although I was regretting giving anything now.

And, as much as I would love to wrap up the story of this scam here, it only continued. And even increased in its ridiculousness. Because next in line for me to meet was the Uncle or Boss of the place. Because the guy I just handed over a week’s worth of dinners to was just some guy who had smeared dirt on my face while most likely calling me an idiot in Hindi. Something they no doubt had a good chuckle about afterwards. Honestly, thinking back, even I find it find it amusing.

Uncle

The Uncle, whom I met on the river bank by the pyres, then requested no less than 18,000 rupees from me (£180) to take photographs at the Ghat. “But I have already paid,” I said. “No, that was a donation now you must pay for the right to take photographs”. Such nonsense I found it difficult not to smile. But the fact he was confident in asking for so much led me to believe others are agreeing to give him this.

The Uncle went on to explain what a great deal it was. And to gain permission from the police would cost far more money and be more time-consuming. So, playing along with the game, making sure I continued to have a successful shoot, I haggled him to 10,000 (£100). He agreed with reluctance, although in his mind, would’ve been ecstatic.

Afterwards, I left to take the photos. Although I still had the pleasure of two men hovering around me (Pawan and a friend he had found that also seemed to think he was getting a payout if he followed me enough). Of course, I was still respectful and discreet around the mourning families. In fact, I hadn’t even made it to the cremations before Raj, Just 15 minutes in, was pushing me to wrap things up. Unbelievable, considering I had practically stood at one location for that time, 100 meters away from the flames. And they wanted how much for this?

Under Pressure

I explained again that I needed to capture the entire process of the cremation, including the rituals and actions surrounding it. Something I had conveyed multiple times in our first interaction. However, disinterested he continued to apply pressure . To which I continually ignored. And after his intensifying agitation passed its threshold, he thankfully disappeared to leave me in peace. Or so I thought.

Because soon after this, the Uncle appeared to pressure me. And again, I ignored it. I couldn’t believe these guys were expecting so much money from me for practically nothing. I felt cheated for handing over the £15 I had already kindly donated to their beer fund. But despite my best efforts to deflect, the pressure continued. I figured these guys were desperate for me to pay them before I disappeared with the downpayment for their next holiday home. Tiring of this behaviour and interference with my job, I reluctantly agreed to finish.

Wheres My Money?

I was now on the 1st floor in between the temple and the cremation ghat and had a group of 5 surrounding me. With grins from ear to ear, I could see these boys were ready for a party. “OK so now it’s time to pay the 1000 rupees?” I stated calmly. “Who should I pay it to?”. The look on Raj’s face dropped instantly. “1000 rupees?” He replied with a look of confusion. “You mean 10,000 rupees?”. “10,000? That’s a bit much for the 20-minute photoshoot don’t you think? I replied. “No, we agreed on “10,000 rupees” stated Raj. “Yes, and we also agreed I could spend as long as I needed here”. “That doesn’t matter, you need to pay me the 10,000”. Raj had now dropped his peaceful spiritual demeanour and had adopted a more aggressive tone.

There was zero chance I was going to give this guy, or any one of the goons there, including Pawan, a single rupee. Fortunately, a few people were taking photographs beside me, so I made a point of asking them in front of the group if they had paid to be there. To which they obviously replied no.

Time to Leave

“You think you’re so smart don’t you” said Raj, his body now visibly tensing with squared shoulders. “No, I just think 10,000 rupees is a lot to pay you for 20 minutes here whilst no one else is paying you anything”, I replied. “The problem with you is you’re using your head, don’t use your head”. He continued. I wasn’t sure what he meant by this. However, it was time to go, so I explained how the conversation was going nowhere and that it would be best if I left. And, after slowly standing up, making sure to politely thank the men for their time, I turned around and began walking away down the stairs.

Without looking back, I descended to the pavement and took a right turn back into the narrow alley. I thought how ridiculous the whole fiasco was and how I was silly to assume that by tipping these guys, they would give me some special privileges other photographers visiting the Ghat would miss. But, you can’t win them all.

You Win Some

The worst part was I hadn’t even taken the photographs I needed. And would need to return. That is, after giving the Doms a little cool-off period. Nevertheless, despite this setback, it was interesting to witness the workings of the scam taking place at the Manikarnika Ghat. And hopefully, by doing so, can help others avoid it entirely.

Unfortunately, that being the end of it all would’ve been too easy. And I couldn’t have been 100 meters up the road when I heard a familiar voice call “Mr David! Wait”. Oh, Jesus, I thought, closing my eyes and taking a deep breath. This is a stubborn cling-on. How this guy believes he’s deserving of a payout after introducing me to a scam was beyond me.

Clueless

“What do you want Pawan?”, I replied coldly. “Where are you going?” he sheepishly questioned. “Well after that disaster, I can’t bloody stay there can I?”, “So I’m of anywhere else”, “And I’m going there without you.” “But, David, what about some help for my time?”. Really? I thought, my eyebrow-raising subconsciously. I looked him in the eye and asked “You truly believe you deserve payment for roping me into a scam?”, “I now need to leave the location without the material I need, if anything you’ve done me a disservice”.

It turned out he truly did consider his selfless efforts as worthy of payment as he continued to follow me for the next kilometre whilst attempting to convince me so. That was until I became fed up and said what I needed to for the reality of the situation to sink into the man’s misguided mind.

Manikarnika Ghat Take 2

Disappointed but largely unfazed by my initial experience at the Manikarnika Ghat, I returned two days later to experience it without the pressure of Varanasi’s con artists standing over my shoulders. Again I approached the Ghat through the city’s ancient mortar capillaries. This time, witnessing several processions passing in just a few short minutes. Death appeared hard at work behind the city’s closed doors today.

Curiously intrigued to tune into the sombre vivacity of the stretcher-bearers, I decided to pursue the heels of a group onto the cremation grounds. I say men here intently because as at no point, at either Ghat, had I noticed a single woman. Later, discovering women cannot participate in the processions beyond their residential streets. And, although there is no clearly defined reason for this, the most common rationalities I discovered were either someone either needed to remain in the house to lok after it. Or the cremations were too unbearable for a woman to witness. Or less commonly opinionated: unmarried women were too pure, or because evil spirits will enter through their hair.

All challenging sensibilities for the Western mind to comprehend. However, this is India, where beliefs and perceptions stretch beyond our questionable horizons. A good starting point is to forget about gender neutral roles.

Following their arrival at the ghat, the cortege passed through the alley separating the ground floor of the crematorium and lay the body of the deceased at the bank of the river. Then, wiping the sweat from their tired brows and exposed skin, the group took a step back to recompose themselves and assess their next moves.

The Process

Once a body arrives at the Ghat, a common ritualistic procedure ensues. Firstly the men will wash the body in the water of the river. Following this, while the body dries, it is time to purchase the wood necessary to build the pyre for cremation. A typical Pyre will consist of between 400-600 kg, depending on the size of the body. The wood used for cremations often varies on the wealth of the families. The Tamarind is the most common variable, used by the poorer castes.

The prices of wood are often negotiable. However, due to the sites monopolistic nature, the cost is often placed beyond the means of many families. And, with no other options, other than dumping the body in the river (which happens frequently), many families are forced to give in to the Dom’s extortionate fees to secure moksha for their loved one.

Cremation Pyres

Once the fees have been negotiated and money has exchanged hands, the labourers, men often stick thin but with the strength of plough cattle, carry the stacks of burdensome logs towards the designated cremation site.

The number of cremation spaces varies with the seasons due to the rising and recessing tide of the river. I was there during monsoon season, meaning the river was high. However, counting the spaces for cremation on the bank alone totalled around 15, with the potential for more if necessary. Also, the additional space on the first floor, means there is ample room to accommodate the high volume of bodies that arrive here daily. Unless there is a pandemic, when I heard multiple reports of queues of bodies lining the streets during covid 19 (the smell must’ve been repulsive).

Once the beds are made, the body is transferred from the stretcher. Prayers are then said for the departed before the body and Pyre are covered in ghee (clarified butter), sugar or kerosine (to aid in ignition). Additionally, sandalwood is added to mask the smell of burning flesh. Another layer of wood is then placed on top of the body. The head and feet often remain exposed. A close male relative, usually the eldest son, with his shaven head, will light a bunch of thin strawlike sticks from the eternal flame and carry it to the pyre to light its kindling.

Ashes To Ashes

The extremities decompose first, often taking less than 2 hours. However, the torso takes considerable time longer. Moreover, as Raj explained in my previous visit, “The chest bones of the men and the hip bones of the women are impossible to burn”, “Due to the men being strong manual workers and the women bearing children”. Meaning it is never possible to destroy the body entirely. Thinking back to my encounter with the dog in the first-floor crematorium, due to its size it must’ve been a bone from the pelvis it was greedily chewing on.

Unlike cremations popularly portrayed in movies and television, the process is not as glamorous or elegant. Not only is one confronted with the blistering skin of the exposed burning flesh. But once the legs and arms reach a certain point of deterioration, they are snapped and folded back towards the centre of the fire. A stark reminder of the true fragility of the human body.

Yet the most striking action of violence comes between the 3-4 hour mark with the Kapala Kriya ritual. The ritual of cracking open the burning skull with a stave to release the person’s spirit.

The fires then continue to reduce the bodies and any remaining wood to ash. The few remaining bones are then collected and either deposited in the river or buried somewhere close to the home of a son. They are never kept in the house. The attendees then wash the dirt from their bodies in the river as the entire process is deemed extremely unclean. Once the embers have settled the ashes are collected by the Doms to be sifted for gold and other valuables before finally they are deposited in the river.

The Cycle of Degeneracy

As challenging as it is to witness these cremations, one must also remember that for members of the Hindu religion, there is no better place to die than Varanasi. And several of those in attendance of cremations testified to their gratitude and relief for their loved ones burning on these banks.

It is unfortunate, however, that the Doms see themselves as above virtue. I understand that for many of the community, there may be bitterness and resentment towards a culture that classifies them as untouchable and confines them to such work. However, this does not explain their attitude of entitlement toward the people who have travelled here to experience the culture of India. An attitude confirmed by the Uncle I had the displeasure of meeting. Stating without hesitancy, “Of course, I am happy about the tourists that come here because it’s possible to earn more money from them.” (implying scamming them).

Such feelings of undue privilege are, however, little more than slavish attitudes that will only serve to maintain their socioeconomic position. Perhaps if they would begin to organise themselves and their services into something that offered more value to those arriving at the Ghat their socioeconomic situation would improve.

The fact the community has a monopoly means they could operate without interruption from outside actors. Meaning they exist in a unique space that could serve as an opportunity for them to become leaders within the community. But again, to expect a group of Indians to perform good deeds in a country with such high levels of competition and corruption would be expecting too much. Even for many of India’s holy sites and men, they are simply not good.

Conclusion

As I sat in a large recessed area consisting of an extra large stone staircase, between the ancient cremation building and a recently constructed building. I couldn’t help but notice how my position between the new, the old and the glowing carbon reflected with astonishing accuracy the point in life at which I find myself.

No longer a child, teenager, or even young man, but still with enough life left in these bones to not categorise them as ancient. I am, for better or worse, in the middle. And whether I can accept the fact or not, as fast as the first half of my life has slipped by, I will reach the end. This fickle body is no longer capable of adverting nature’s tortuous parody in a tragic drama we have no choice but to play our part.

What am I to do with the half-life that remains between me and the inferno of Armageddon? And to what extent do my actions matter? Is consciousness a fundamental component of the universe? Or are we merely biological machines fulfilling tasks in line with the survival instincts coded into our DNA? Questions that would circle my mind for the remainder of my time there, and which continue to echo in the chamber of my psyche weeks later.

Varanasi, for all its qualms and faults, has still bestowed onto me an invaluable perceptiveness of what it means to be human. By unapologetically holding me by the collar and forcing me to confront the inevitable decay of life, the person who arrived in this city will not be the same person who left.

Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats, Varanasi’s Burning Ghats.